Originally from Sao Paulo, André Golabek, was the real creator of a government app in Venezuela that Maduro sold as national and that captures millions of citizens’ data. He also founded Venqis, a political communication company that advised campaigns later mentioned by hundreds of fake accounts that spread disinformation and propaganda in favor of Bolivarian candidates to governorships in Venezuela and officials in Panama, Bolivia, and the Dominican Republic. Twitter knocked down almost all of them, but a new batch was created to hype the current presidential candidate of Panama, José Gabriel Carrizo.

By CLIP teams, Cazadores de Fake News, with the support of UOL

During the months leading up to the Venezuelan regional elections of November 21, 2021, some of the opposition candidates were challenging the certainty of yet another victory of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) in multiple governorships.

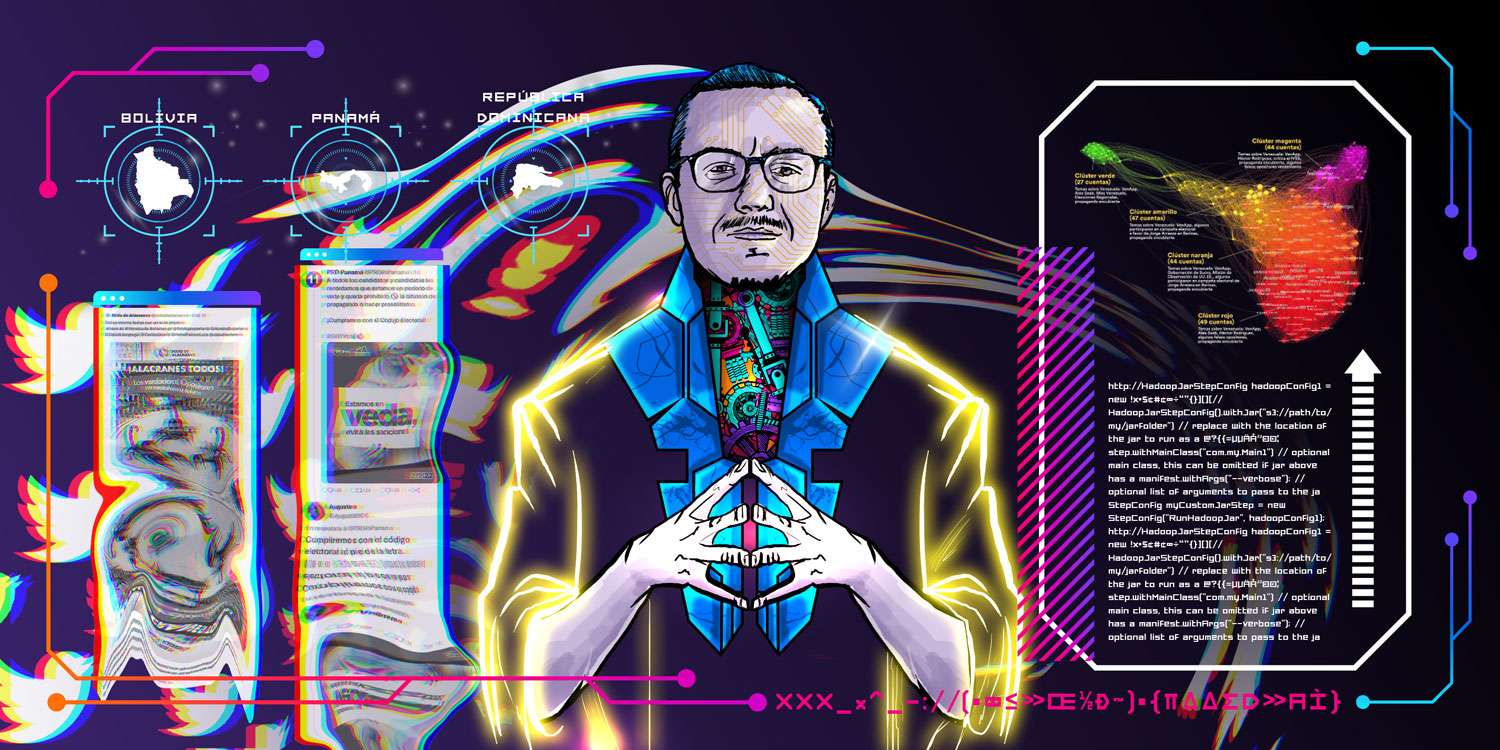

In December of that year, a piece by Cazadores de Fake News -an ally in this cross-border journalistic collaboration called Digital Mercenaries – found that accounts denounced for hyping in a coordinated manner PSUV candidates Jorge Arreaza, who aspired to governor of Barinas, Héctor Rodríguez, of Miranda, and Carmen Meléndez, of Caracas Capital District, and with few followers, were part of a troll farm, that is, they formed a group of inauthentic accounts adopting fictitious personalities to covertly pollute the conversation online. Cazadores identified in that study that at least 187 active Twitter profiles -later found to be as many as 357- were participating in an inauthentic and coordinated way in the online electoral conversation, praising pro-government candidates, rejecting opponents, or urging them to withdraw from the elections and join the decision of some opposition parties to boycott the elections.

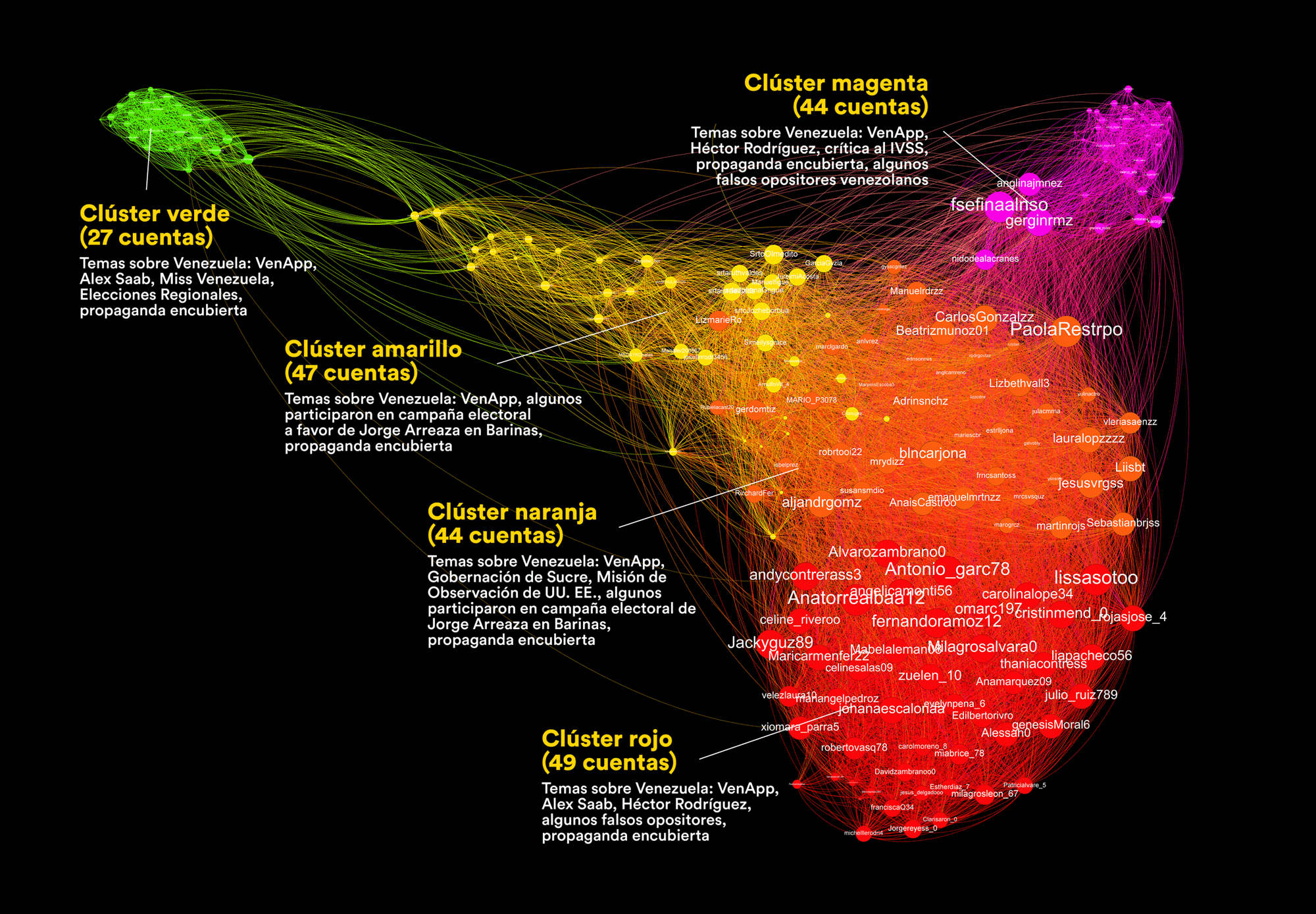

In the following tracking map of 211 Twitter profiles, which resembles a fishing net, each dot or «knot» represents a troll account, while each line connecting these «knots» indicates that one account was following the other. The colors of the knots vary depending on the theme that each account was promoting. Thus, magenta accounts acted as false opponents disseminating covert propaganda; yellow ones promoted content favorable to candidate Jorge Arreaza in Barinas, and red ones coordinated to generate content favorable to the candidate of Miranda state, Héctor Rodríguez.

Here are three of the fake accounts in action: in favor of Arreaza (left), unfavorable to Freddy Superlano, his opponent in Barinas (center) and sowing doubts about the news that the International Criminal Court would investigate Venezuela for violation of human rights (right):

In another study the following April, Cazadores found that the fake accounts or trolls numbered at least 357 and were simultaneously participating in public discussions in Venezuela, Panama, Dominican Republic, and Bolivia. The piece included another surprising finding. Beginning in February 2022, 147 of the troll accounts began inviting citizens – in a suspiciously coordinated way – to join VenApp, a previously unknown Venezuelan social network that had appeared days earlier on billboards in Caracas.

A few weeks later, confirming the investigation of Cazadores, Twitter removed 352 of these 357 profiles, making in clear that they weren’t being used by ordinary users, but that a single agent or company operated them in a coordinated manner to manipulate not only the debate on the elections in Venezuela, but also campaigns in Bolivia, Panama, and the Dominican Republic.

Now, Cazadores de Fake News, in alliance with 22 media outlets and four digital research specialists covering the region, coordinated by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism, CLIP, found that new accounts with similar characteristics of the farm suspended by Twitter continue to support Panamanian president Laurentino Cortizo and his vice president José Gabriel Carrizo today.

In addition, we were able to take a closer look at the Panama-based political consulting firm that previous investigations had already pointed to as the suspected puppeteer behind the network of fake opinion-makers: Venqis and its owner, the Brazilian Andre Golabek. Thanks to documents that were sent anonymously to this journalistic alliance, we also raised the question about the risk of an e-government application in Venezuela being used to capture citizens’ data for electoral purposes.

Fake endorsements of the PRD in Panama

Panamanian tweeters reported accounts that appeared to be fake posting in May and November 2022 and in February and April 2023. Following the same method used by Cazadores to locate the fake profiles suspended by Twitter, this journalistic alliance was able to identify at least 100 other troll accounts posting content favorable to Vice President José Gabriel Carrizo, now a presidential candidate for the 2024 elections. It is noteworthy that some of the inauthentic accounts detected in 2021 and 2022 and suspended by Twitter had also promoted Carrizo. Here are some examples of how they praise Carrizo and denigrate one of his competitors, former president Martin Torrijos:

Of this new generation, with at least 100 new active troll accounts in Panama, 15 were created in November 2022, 22 the following January and 63 last March. On average, they have less than 2 followers and have made only 2 «likes» in the time they have been active.

Venqis y Golabek

This and previous investigations have found clues that Venqis, S. A., a Panamanian political communication firm, and its president André Golabek Sánchez, originally from Brazil and proxy of other companies in the digital world, could have been moving these fake accounts.

Golabek Sanchez was born in Sao Paulo in 1977 and is known in that country’s courts for multiple past shenanigans. A search in the Sao Paulo Court reveals that he has had at least 19 lawsuits, three for labor matters, nine for tax matters and six more for civil matters, of which one is an eviction.

He has also faced criminal proceedings. When judicial officials tried to locate him for a 2010 assault complaint, reiterated in 2013, they could not find him. In 2022, the Sao Paulo Court declared the investigation void because of the time elapsed without a summons, since the maximum sentence for this type of crime in Brazil is one year. Court records do not specify what type of aggression the case referred to. Golabek had sent documentation to several media, claiming to be in good standing with the justice system in Brazil and other countries.

On the business side, his career is also not without blemish. He created Sauber Maxx Indústria e Comércio Ltda. in 1995, which closed in 1998. Then he set up Jaguar Comércio Exterior Ltda, a company that was declared ineligible in 2005 for «irregular practice of foreign trade operation». The Receita Federal documents, however, do not detail what was the irregular operation that led to the closure of the business. In 2014 he was already in the software business, with the company Popstore do Brasil, which is still active and headquartered in a privileged neighborhood of Sao Paulo.

Now this journalistic investigation found coincidences between countries and periods in which Venqis, Golabek’s Panamanian firm (or other related ones), advised political or institutional actors with the inauthentic and coordinated operations detected by Cazadores and eliminated by Twitter.

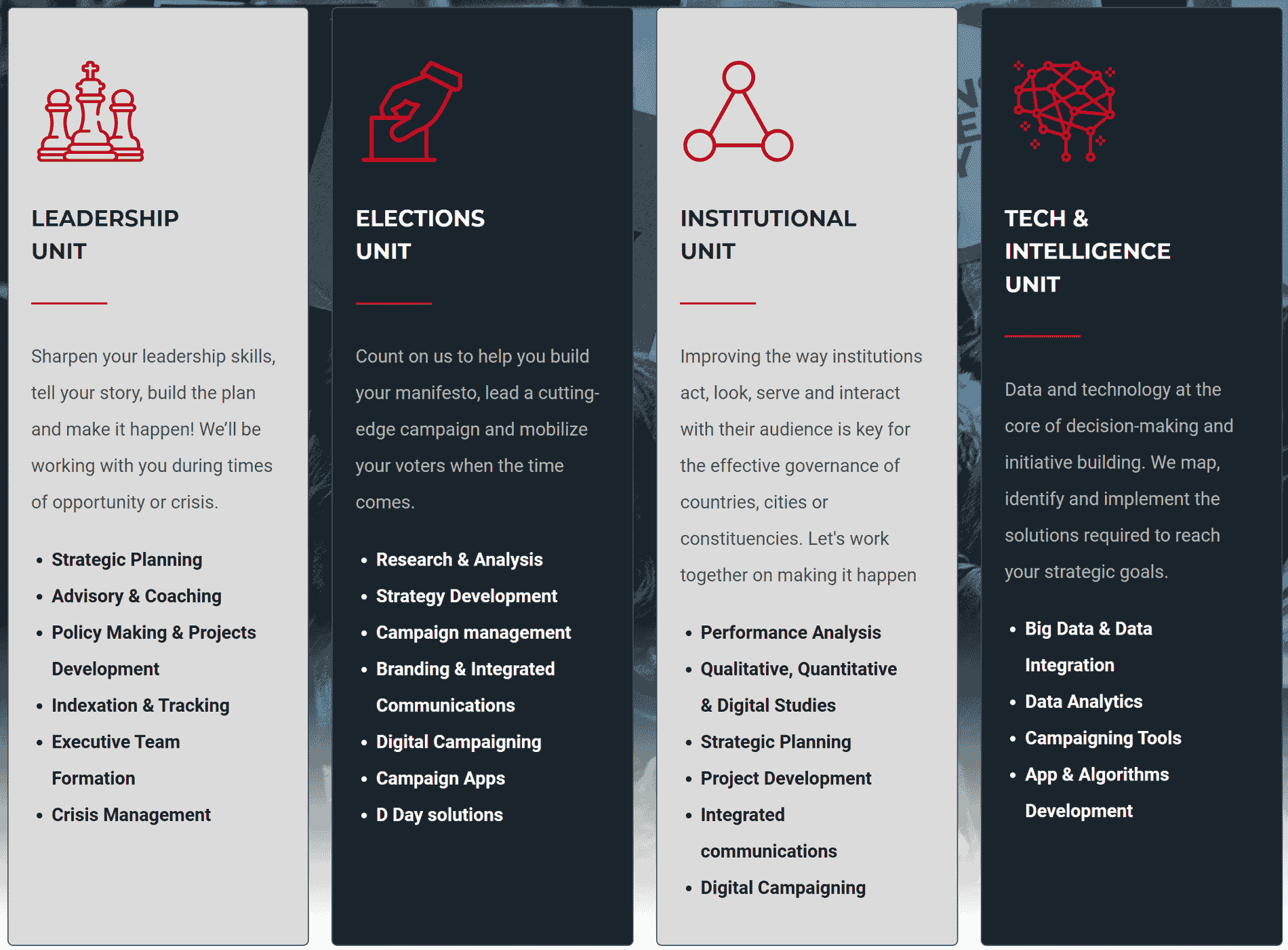

In the description of the services available to candidates in electoral processes on its official website, Venqis offers strategic planning services, crisis management, campaign management -including digital ones- and performance evaluation. Additionally, it offers data analysis services, app development, algorithms, and big data management, which suggests that it has the resources, tools, or experience to process large collections of millions of data:

The company demonstrates experience with the development of e-government applications (apps) that enable citizens to connect with their governments – so that the latter may hear and more effectively address their needs – and that are also capable of storing huge volumes of user data.

For example, digital traces connect Venqis and other companies related to Golabek with the development of an app for the Ombudsman’s Office of Panama, two for the National District of the Dominican Republic -Planeamiento ADN and MiSantoDomingo- and also the aforementioned VenApp in Venezuela which, as mentioned before, was strongly publicized by the network of fake Twitter accounts. It is this last case that seems to suggest that the connection between the coordinated inauthentic operations tested in Venezuela and Venqis might not be coincidental.

On May 19, 2022 VenApp was presented by Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro as a digital tool «designed by Venezuelans». This journalistic investigation, however, found that the app could be downloaded from the profiles of another company called Tech & People in the Play Store and the App Store. That same year, the profiles changed their name to Cyber Capital Partners Corp. Looking for Tech & People’s privacy policies – something every app user should do when downloading an app to make sure it is not a data-trap – we found that they were hosted on the website of another company, this one called Nolatech.

Golabek, president of Venqis S. A., is behind these companies. He is the legal representative of Nolatech S.A., an expert firm in the creation of websites and e-government applications based in Panama. He is also director of Tech & People Solutions TPS, based in the Dominican Republic, and a former director of the Panamanian company Cyber Capital Partners Corp. (The latter changed its name to Amyr Trading Company Inc. in September 2022, but Golabek is still its legal representative). So VenApp was not designed by Venezuelans, but by a Panamanian firm connected with other Panamanian firms and one Dominican firm, all connected to the name of Golabek, the head of Venqis.

Billboards in Caracas and online networks invited Venezuelans to download the VenApp, a tool for people to report failures in public services and other problems of daily life. This application came to complement the trio of digital platforms controlled by the Maduro government -together with Sistema Patria and Sistema 1×10 del Buen Gobierno- capable of managing and storing large amounts of citizens’ data and which the government has presented as channels for more effective government, as announced in this video.

Considering that the Venezuelan government has faced accusations of irregularities during electoral processes and of having implemented tactics of digital authoritarianism including cyber-surveillance, censorship in social networks and the monitoring and compensation of tweeters who amplify government propaganda, it is worth asking whether the data collected by VenApp could be used to give the ruling PSUV an advantage in the next electoral contest.

Is VenApp a data vacuum cleaner designed to win elections?

According to its privacy policy, VenApp can request from each user a considerable volume of personal data, including basic personal identification elements such as name, email and phone number, as well as more precise details if provided by the user during the sending of reports or complaints, such as their full address and the exact location of the place from which reports or complaints are sent through the app regarding for example failures in public services or acts of corruption.

Here we can see that when VenApp users make online reports, the app asks them for their personal data such as name, address and georeferenced location of the complaint:

As this huge data capture takes place in a country with a significant lag in the development of transparency and data protection laws, Venezuelan non-governmental organizations and digital activists have expressed concern that it could be used to boost the efficiency of the Chavista electoral machinery.

Access to large volumes of personal voter data collected by VenApp, including geolocated incidences of public services, could allow the Venezuelan government to micro-segment the electorate, that is, to divide it into very small groups that could be targeted with personalized messages in future electoral campaigns, based on their interests, concerns, and needs. By possessing specific information on the needs or deficiencies in public services in specific municipalities or parishes, the governing party could use this data to enhance the effectiveness of its campaign strategy in a localized manner.

A precedent in Latin America gives rise to these concerns about an e-government application acting as a «data vacuum cleaner» that can then be offered to political parties during an electoral process. This is the case of Sosafe, an app that feeds on reports from Chilean citizens and was developed by Instagis, another company expert in big data, like Venqis, which has also been a provider of software and tools in Chile during election periods. According to an investigation by Ciper Chile, Instagis supplied the software that was used to georeference the areas where Sebastián Piñera’s campaign had to intensify door-to-door campaigning, to ensure votes in the most critical sectors.

The question regarding VenApp and its possible use of data so far was merely speculative. However, at the beginning of 2023, this journalistic alliance received a package of anonymous information from the VenApp hub interface, a leak consisting of dozens of screenshots of the different sections of the administration panel, which, after a process of data verification, we concluded to be authentic and legitimate content. The obtained leak revealed that the information this platform stores about its users also includes other sensitive data. This data, of high partisan and electoral interest, can be provided by users and includes elements such as the Carnet de La Patria (homeland card) number and the assigned voting center.

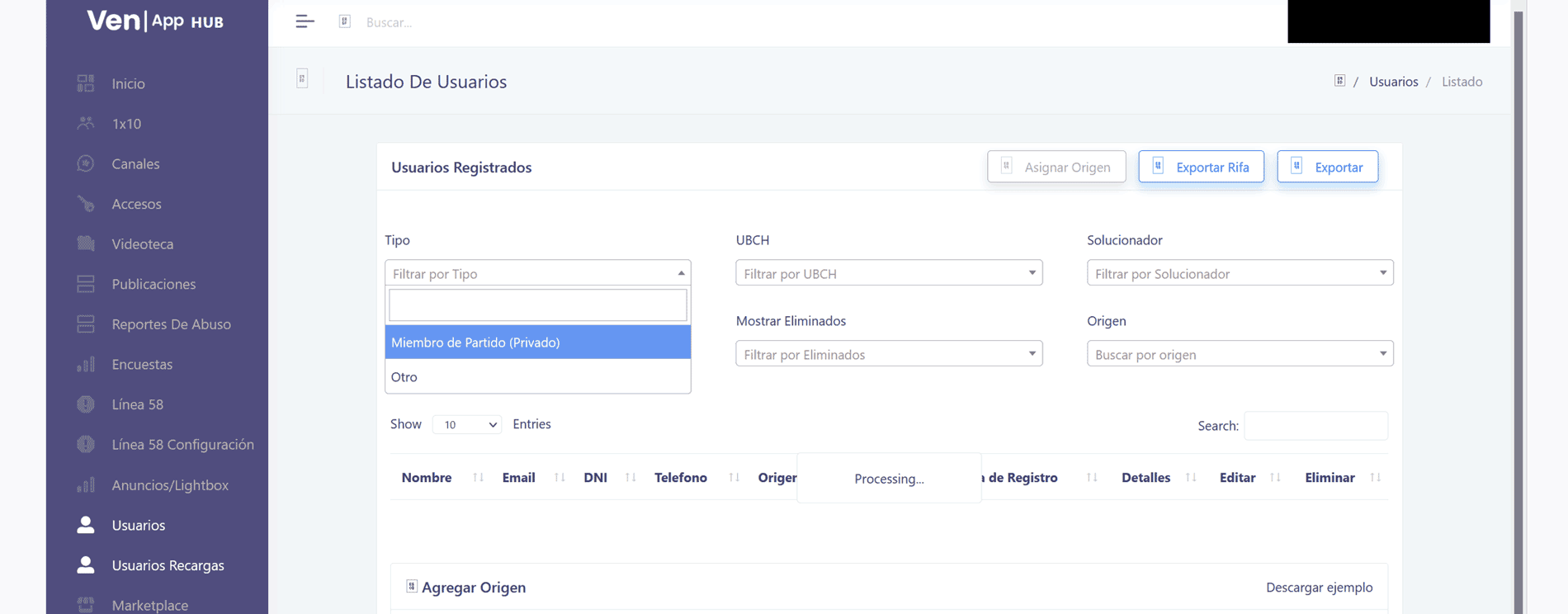

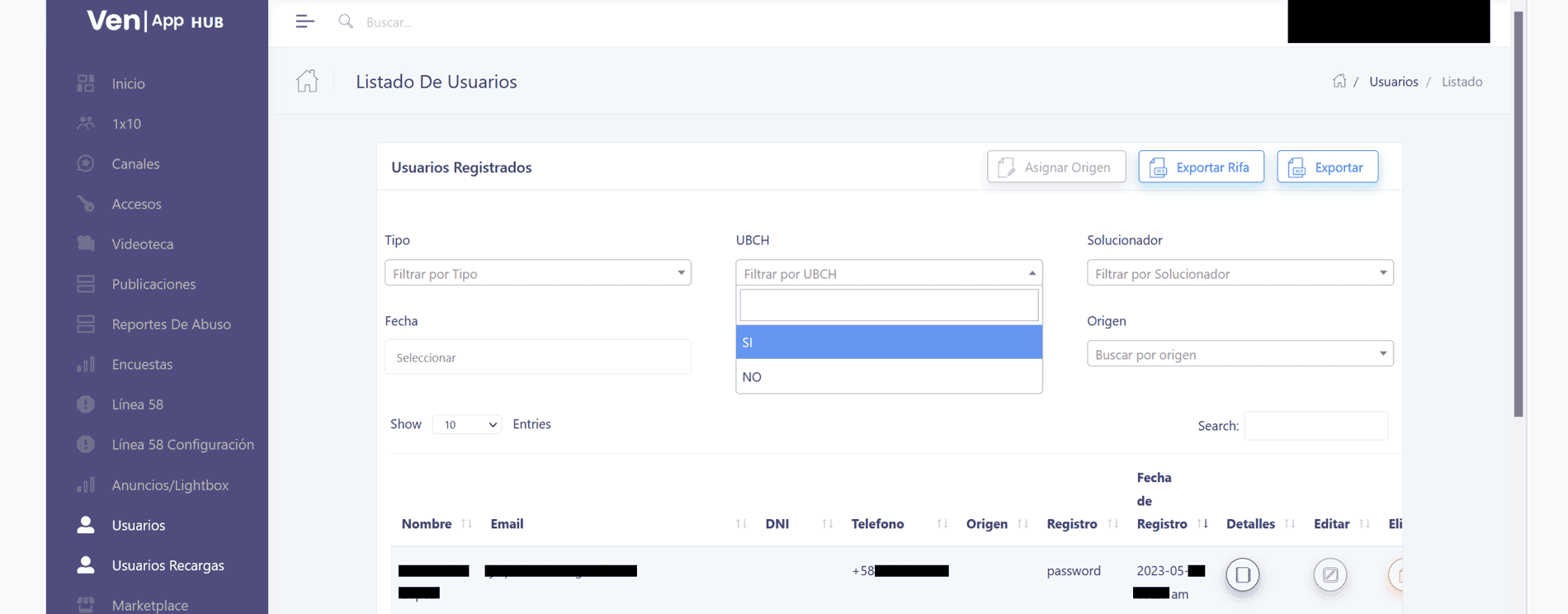

As can be seen here, in the moderation panel of the VenApp application, users can be classified according to several fields, two of which are of organizational and electoral relevance for the PSUV: the user’s affiliation to the Bolivar Chavez Units UBCh and whether the user is a «Party Member»:

However, the VenApp hub does not explicitly register information on users’ political party affiliation.

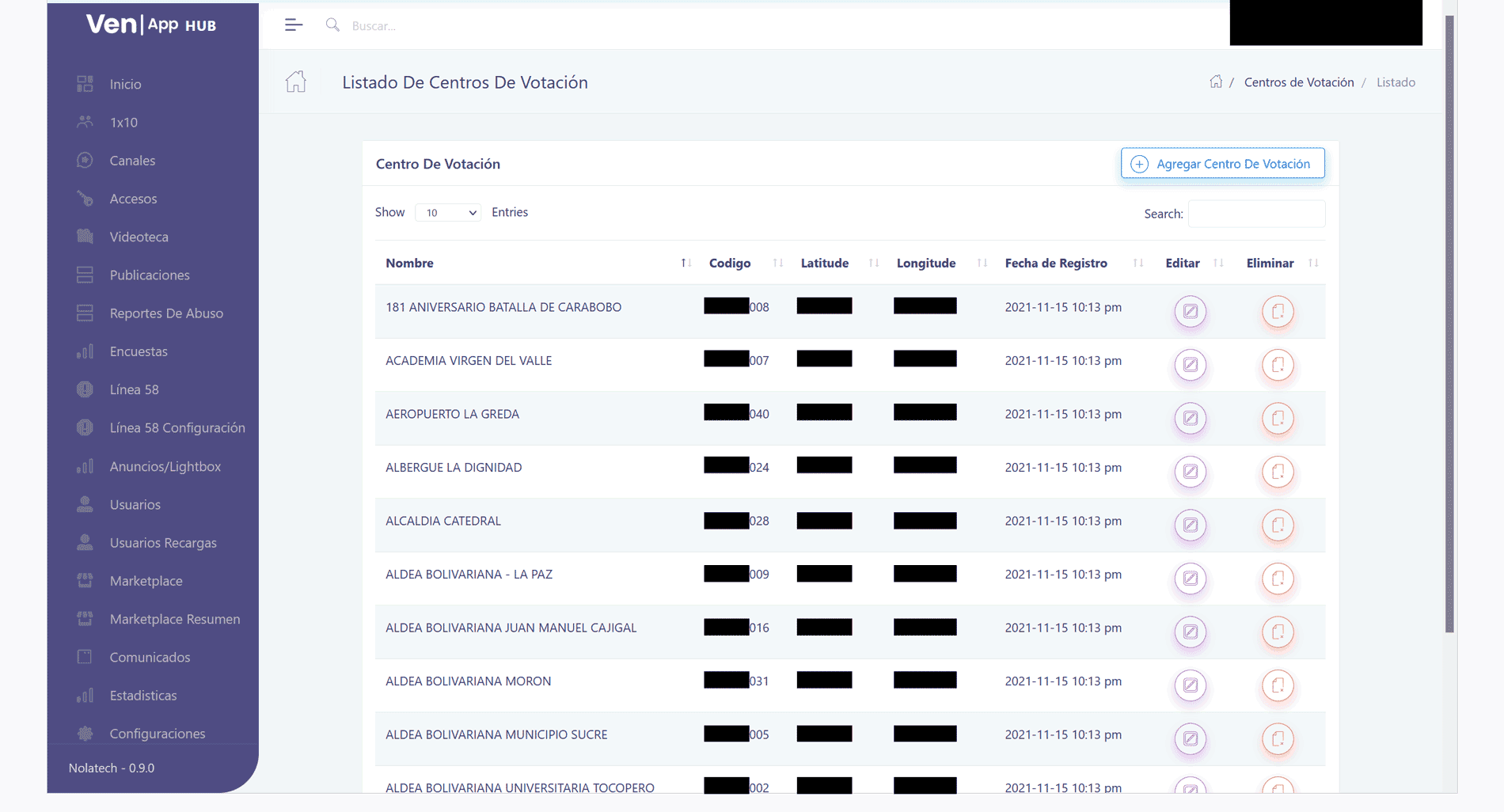

In the same moderation panel, there is a section in which 13,469 voting centers are identified with their geographic coordinates. This list was included in the application in November 2021, three months before the name VenApp was mentioned on Twitter, in a coordinated manner, by the network of fake accounts, and six months before it was officially presented by President Maduro on national television.

Venqis’ involvement in the development of VenApp and in the PSUV campaign for the 2021 regional elections revealed its connection with the ruling party and raises questions about possible conflicts of interest. Therefore, when Nicolás Maduro assured that VenApp had been developed «by Venezuelans», it is possible that he wanted to divert attention from the fact that one or more of the companies related to Golabek were involved in the development of VenApp.

It is not possible to attribute with certainty the creation or operation of fake accounts to Venqis. However, the revelation of this leak, that citizens can be classified by voting stations, raises doubts about the ethical handling of VenApp users’ personal data and uncertainty as to whether it could be exploited in favor of the PSUV in the upcoming presidential elections.

Venqis in the Bolivian presidential campaign

Another controversy in February 2022 in Bolivia involved a Venqis consultancy in communications. According to information from Página Siete, Venqis participated in a bidding process for a contract to carry out an advertising campaign on the Astillero exploratory block, an area with natural gas reserves that coincides, at least partially, with the natural reserve of Tariquía, in the department of Tarija.

A confidential document from the bidding process for the campaign revealed that one of the objectives of the communication strategy was to «promote a change in the perception of exploration activities in protected areas and to communicate compliance with the applicable regulations for the Astillero project and its benefits».

In Tarija, several opposition members of congress expressed their concern about possible conflicts of interest, due to Venqis’ participation as advisor to the presidential campaign of the current Bolivian president, Luis Arce in 2020. The Cazadores de Fake News investigation from April 2022 documented how the troll farm attempted to manipulate the conversation on Twitter to counter online content unfavorable to Venqis.

A subset of ten accounts belonging to the same troll farm that had posted inauthentic content during Venezuela’s election campaign began tweeting messages defending the Panamanian firm. The accounts also attacked with responses to Bolivian media that had suggested that Venqis may have been involved in a corruption or improper payment scheme, highlighting the «ignorance» of the deputies in charge of investigating the case, and suggesting that local journalists «get carried away by bribes,» among other accusations.

Months earlier, some of these fake accounts had posted messages in support of Luis Arce, Bolivia’s current president, and promoted content related to Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos’ (YPFB) Renewable Diesel program. Here are examples of how fraudulent accounts that were suspended by Twitter responded to Venqis-related tweets posted by Bolivian accounts on February 15, 2022:

But the controversy began to fizzle out when Óscar Salazar, YPFB’s communications director, claimed that Venqis had not won the bidding process, which had ended without contracting. Golabek, the president of Venqis, admitted having supported Arce’s campaign because he said he believed in his political project. He assured that he did not receive any payment for services rendered during that electoral campaign and clarified that he had only participated in a communication contracting for YPFB Chaco – the «Renewable Diesel» campaign – but that this had ended in March 2021.

However, this investigation uncovered a document that confirms Venqis’ participation, at least partially, in the presidential campaign in favor of Arce. In a letter dated November 11, 2020, available on the transparency website of Panama’s general directorate of public procurement and delivered as part of a Venqis proposal for the redesign of a website for the country’s Ministry of Economy and Finance, Antonio Jadue Amarayo, president of the Palestinian Community of Bolivia, assured the Panamanian ministry that Venqis developed the campaign website luchopresidente.com, «as requested”:

On Jadue’s personal Twitter profile, he appears in several photos in the company of both Venqis executives – including Andre Golabek – and President Arce, a few weeks after he won the October 18, 2020, election race.

Fingerprints linking campaigns

There is other evidence available from open sources that proves that Venqis and other companies linked to Andre Golabek Sanchez were part of political campaigns and communications consultancies in precisely the same countries and campaigns where the activity of dozens of fake Twitter accounts was detected.

A proposal submitted by Venqis in October 2020 – in the middle of the pandemic – to the Autonomous University of Chiriqui, to develop a strategic communication program for distance education, is available on the website of the transparency file of the General Directorate of Public Contracting of Panama. The proposal reports that the company provided institutional advisory services to several Panamanian government entities, to the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) -which led Laurentino Cortizo to the presidency in 2019-, to the Panamanian presidency itself and to the mayor’s office of the National District of the Dominican Republic.

Reports from the Electoral Tribunal of Panama reveal that Venqis was hired by the PRD between April 2018 and March 2021, and received 21 checks totaling $94,160 for «professional communication and social media management services», among whose tasks include active listening on platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

The connections between communication consultancies and digital campaigns of Venqis, Nolatech and Tech & People in Latin America have been confirmed by digital footprints left by website domains, obtained from open sources such as SecurityTrails.com. Coincidences in IP addresses associated with digital communication contracts, e-government apps such as VenApp and electoral campaigns promoted by the company, left evidence of their work in Panama, Venezuela, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, and Honduras.

When in early 2022 the troll farm was detected pushing propaganda and disinformation covertly in Venezuela, and after identifying coincidences with the company’s activity in Venezuela, Bolivia, Panama, Dominican Republic and Honduras, the need arose to check if there were troll accounts on Twitter that could have driven -covertly- campaigns for the company’s clients in Bolivia, Panama, Dominican Republic, and Honduras.

Indeed, it was almost all confirmed: fake accounts from the same troll farm posted content in support of Jorge Arreaza, PSUV candidate in Venezuela, and President Luis Arce and the Diésel Renovable program in Bolivia. Other trolls, also linked to the campaign in Venezuela, posted responses directed at David Collado, former mayor of the National District and current Minister of Tourism of the Dominican Republic, José Gabriel Carrizo, current vice president of Panama and the Democratic Revolutionary Party of Panama.

For example, accounts that at the end of 2021 identified themselves as users from Barinas, Venezuela, publishing socio-political content for this audience, changed their location to Panama at the beginning of 2022, to promote the Democratic Revolutionary Party and the Panamanian vice president, José Gabriel Carrizo. Others that had attacked Bolivian media in February 2022, raising their voices during the Venqis controversy in that country, in April 2022, deleted all their tweets, changed their location to Panama and followed or were followed by other troll accounts that published propagandistic content in favor of the PRD.

Here for example, you can see an account that in September 2021 spread propaganda in Venezuela (left, center) and in March 2022, did the same with the Democratic Revolutionary Party of Panama (right):

The exception to the rule was Honduras, in which case no fake accounts with similar characteristics were found.

Twitter’s challenges in the face of manipulation operations

Those who manage social networks are often clear about manipulation on their platforms through fake accounts to distort the conversation and spread disinformation.

That’s why this team interviewed Yoel Roth, who held the position of Director of Trust and Safety at Twitter – the team in charge of drafting and consistently enforcing anti-spam and manipulation policies on the social network – before Elon Musk acquired the platform. While in this position, Cazadores de Fake News published the two reports on the network of 357 troll accounts polluting online conversations for audiences in Venezuela, Bolivia, Panama, and the Dominican Republic, and they sent the reports to Twitter.

Roth acknowledged being aware of several cases similar to the one reported by Cazadores in 2021 and 2022, but since he could no longer access Twitter’s internal records, he said he could not provide context on the network’s suspension. «On at least one occasion, Twitter officially disclosed activity originating in Venezuela that appears similar to that identified in those reports. The activity we identified did not stop, but our investigations continued until the team responsible for them was disbanded following Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter,» Roth said in the interview. He resigned from his position in November 2022, amid a wave of staff resignations and layoffs.

We asked him to tell us how, in his experience, such influence operations affect citizens. «People go to social networks to talk about politics and current affairs, and they should be able to do so without worrying that what they see is the product of inauthentic manipulation,» he said, arguing that it is the social networks themselves that are in the best position to identify and disrupt these manipulative operations in their environments. «They have to do so in the interest of promoting a healthy and credible civic discourse. Otherwise, they will be less trustworthy, less secure and could lead to the spread of disinformation that incites violence.»

Venqis’ director, André Golabek Sánchez, was contacted by our team via email on July 12, and was sent a questionnaire with six questions to learn his versions of the events described herein. However, as of the date of publication of this article, we have not received a response to our inquiries.

Download here a Glossary that specifies the meanings of words or phrases related to the digital phenomena used in this research.

Mercenarios digitales es una investigación de Chequeado (Argentina), UOL y Agência Pública

(Brasil), LaBot (Chile), Colombiacheck y Cuestión Pública (Colombia), CRHoy,

Interferencia y Lado B (Costa Rica), GK (Ecuador), Factchequeado (EEUU) Ocote

(Guatemala), Contracorriente (Honduras), Animal Político

y Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad (México), Confidencial y República 18

(Nicaragua), Ojo Público (Perú), El Surti (Paraguay), La Diaria (Uruguay) y tres

periodistas investigativas (Bolivia y España/Colombia); las organizaciones de

investigación digital Cazadores de Fake News (Venezuela), Fundación Karisma

(Colombia), Interpreta Lab (Chile), Lab Ciudadano (Honduras) y DRFLab (EEUU);

y estudiantes del curso de maestría Using Data to Investigate Across Borders de la profesora Giannina Segnini (Universidad de Columbia EEUU), con la coordinación del Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística, CLIP. Revisión y asesoría legal: El Veinte.

Con apoyo financiero de Free Press Unlimited, el programa Redes contra el silencio (ASDI), Seattle International Foundation y Rockefeller Brothers Foundation.

Cazadores de Fake News investiga a detalle cada caso, mediante la búsqueda y el hallazgo de evidencias forenses digitales en fuentes abiertas. En algunos casos, se usan datos no disponibles en fuentes abiertas con el objetivo de reorientar las investigaciones o recolectar más evidencias.